Interview and photos by Liz Joseph, garden and education coordinator at Heifer Farm

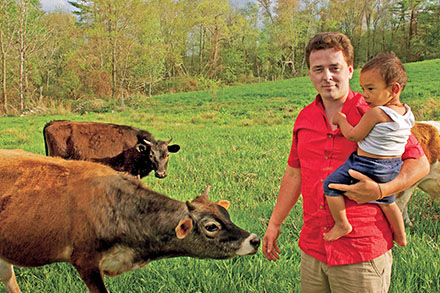

Drive up to Kittredge Farm in central Massachusetts, and you'll find a restored farmhouse with a post-and-beam porch, long hoop houses growing an abundance of seasonal produce and a farmer feeding a herd of beef cows with the help of his 2-year-old son. It's a classic, pastoral scene of a hardworking farm family.

Stay awhile, and you'll notice a few things that are less common of a New England farm -- the mineral depot in the barn, for example, where soil amendments are stacked, pallet after pallet. Or the frequent chiming of a cell phone as people call to invite the barefooted farmer for a speaking engagement or to plan a grocery store flash mob to inspire nutrition awareness.

This busy and sought-after farmer is Dan Kittredge. With roots growing up on an organic farm and being involved with the food movement for 35 years -- that is, his entire life -- he's founded an organization that is changing the way we think about our food, our health and, most importantly, the soil under our feet. The organization is the Bionutrient Food Association (BFA), and growing the healthiest of food on the healthiest of soils so people can be their healthiest selves is what it's all about.

WORLD ARK: What is the mission of the Bionutrient Food Association?

DAN KITTREDGE: The mission of the BFA, as we call it, is to increase quality in the food supply. There's been a dramatic decrease in the average nutrient levels of crops over the past 80 years, since the USDA [Department of Agriculture] began documenting them--anywhere from 25 to 85 percent, depending on the crop and the nutrient. Concurrently, there are epidemic levels of degenerative diseases in humans, and there are strong correlations between nutritional deficiencies in crops and degenerative diseases in humans. We can systemically address these chronic health issues in humans through good agricultural practices that build soil fertility and get real nutrition in our food.

What led you to start this organization?

I started the BFA because I wanted to be a better farmer. The crops I grew regularly succumbed to pests and diseases. A crop that gets the nutritional compounds it needs can flourish and resist pests and diseases. A crop that doesn't will get sick. If nutrients are not in the plant--because they aren't in the soil to begin with or because the plant cannot access them due to agricultural practices-- then we humans aren't getting them either. There are 65 different elements in the human body that are necessary for our bodies to function. We evolved to get these elements from our food, and our food only gets them from the soil. Most soil tests only report out about three of these elements--nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, or NPK. The Bionutrient Food Association is helping farmers address the full spectrum of elements and build a biological system in the soil, so they can grow healthier crops for healthier food.

What is a bionutrient exactly?

A bionutrient is a biologically derived nutrient, a nutritional compound that has a health-giving attribute for humans. It's different from synthetic nutrients created in a lab, which often are not easily assimilated by the body; for example, vitamin D added to a gallon of milk or fl our that's been fortified with thiamine. Bionutrients are found naturally in our food when soils are healthy. How is this different than nutrient density? Nutrient density is a term used in food science that refers to one food having more or less average nutrition per unit calorie than another. So kale, for example, is more nutrient-dense than rice because it has, on average, more nutrients per unit calorie than rice does. What we are interested in at the BFA is identifying which bunch of kale has more nutrients than the other bunches of kale on the shelf at the grocery store, farmers market or wherever people get their food.

It's about quality. We want to help farmers grow the bag of carrots with the most carotenoids, vitamin C, vitamin A, and so on because that's the bag that consumers will want to buy to keep them healthy. It's also the bag that is the most flavorful because nutrition and flavor go hand-in-hand.

So the flavor of food is determined by how nutritious it is, and the nutrition of food is determined by soil health?

Absolutely. Unequivocally. Does the food you eat affect your health? Does the soil that the plant eats affect its health? Yes. Categorically.

How do soils become degraded?

If you look at it historically, major agricultural civilizations rose up in river valleys, from the Tigris to the Nile. This is because river valleys have an annual remineralizing process during the spring floods. Now soils are becoming weathered because we are taking thousands of pounds of crops off the land each year and not putting back what has been removed. The best metaphor is understanding that a crop, say an apple, is attempting to put the best nutrition into its seed. In nature, those seeds fall to the ground randomly, and nutrients are cycled back into the soil. In modern agriculture, all those seeds, nuts, fruits and roots are harvested off the soil, and after 10, 50, 100 years, our agricultural practices are quickly, easily pulling critical elements out of the soil. We're effectively mining the soil of nutrients. North Africa is a great example--it used to be a fertile land that provided food for the armies of the Roman Empire. Now it's the Sahara Desert. The advent of conventional agronomy has further contributed to soil degradation and demineralization because plants receive nutrients from chemical fertilizers. When you bypass the soil you get a crop that may look like a tomato, but it doesn't have the same flavor or nutrition as a tomato that is rich in biologically derived nutrients from the soil. Chemical fertilizers also burn up organic matter in the soil to release nutrients, and when the organic matter is gone, they don't work anymore. That soil has been denuded.

What kind of agricultural practices improve soils?

Plants have evolved in a living system, a biological system. There are a number of environmental conditions that must be present for a plant to flourish. The first piece of the puzzle is the soil life. It's the microbes in the soil -- the bacteria and fungi -- that primarily feed the plant, similar to the digestive tracts of humans. Agronomic practices that kill off soil life -- chemical fertility management, tillage, pesticides -- are systemically detrimental to crop health. Microbes need air to breathe, water to drink, food to eat. So as farmers, we need to create conditions for soil life to flourish. Maintaining hydration, aeration and organic matter levels are paramount.

Plants also need critical minerals and elements -- copper, zinc, molybdenum, cobalt, chromium, iodine, selenium and so on -- just as much as we do.

So soil remineralization is often needed to address mineral deficiencies present in a soil. What are ways to address mineral deficiencies?

I'm of the opinion that between various rock dusts and seawater, we have the full spectrum of elements necessary to revitalize any soil on the planet. You can certainly also buy amendments -- limestone, rock phosphate, greensand, humates, gypsum -- in a bag from a supplier based on whatever is needed, which can be determined by a full-spectrum soil test.

What are other benefits of this work in addition to increasing human nutrition?

Healthy soils yield plants that are healthgiving for us and indigestible to some insects and pathogens from which many farmers suffer. Reduced pest and disease pressure means an enormous savings of time and inputs, which leads to greater economic viability for the farmer. There's huge potential for an increase of yields as well. It's estimated that the average tomato plant in the United States produces between 5 to 8 pounds of tomatoes per year. The world record tomato plant produces more than 600 pounds. Farmers regularly can produce 20 to 50 pounds of tomatoes per plant if they are growing healthy plants.

Another exciting corollary benefit is the potential to ameliorate the effects of climate change. It's been documented by numerous researchers all over the planet on various continents that well-managed soil and healthy plants can increase soil organic matter by half a percent per acre per year. Organic matter is essentially carbon stored in the soil that was once in the atmosphere, and is made through the symbiosis between plants and microbes: the bacteria and fungi.If we were to apply good biological management in agriculture across the planet, we could functionally sequester all the carbon that's been added to the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution in the 1750s in just three or four years.

Are there ways for people to get involved in this work?

The BFA is designed to empower action. We have local chapters starting up all over the country. We offer free introductory lectures, we can host courses. People who want to educate themselves -- local gardeners, homesteaders, farmers, chefs, eaters -- can contact us to set up a workshop. Our website also contains audio recordings from past workshops and a bibliography with books that have laid out a lot of these principles.

What is your vision for the future?

I've worked in the fields in India with farmers whose crops were failing. These farmers were aching for support, knowledge and understanding of how to build their soils and grow healthier plants. If we can convey principles of biological management to farmers all over the planet who are struggling to grow crops on weak soils, if we could use local materials, local rock dusts, seawater, sea salt to systemically remineralize soils, that would be extremely empowering. My goal is to build a functional organization that can serve people who want to grow and to access good food. At the BFA, we want to create a reality with real solutions, real options. I believe that the health of our kids, and the planet, depends on it.